I am currently gathering notes for the more exhaustive post on the philosophical strengths and limitations of the sicentific method I promised a while ago. The debates I have fought since the first, stubby, provocative post showed me that not as many as I expected are familiar with the basics of logical reasoning and the fundamental so-called Ways of Knowing (a concept of ToK, a subject unique to the International Baccalaurate, described briefly in an earlier post), so I think it is essential to make a thorough introduction to those first; I will also need quite some time to recap and organise what has been discussed since, and to try to give an organised, all-encompassing account of the topic... What I am saying is that I expect that this will take a long time to complete. (Luckily, it is rather calm on the schoolwork front at the moment.)

Until then, have a think about what makes paleontology a 'science'. (This is another topic of interest of mine, and I might challenge it sometime later.)

Monday, 28 January 2013

Sunday, 20 January 2013

PalQuiz 2

First the

answers to the first quiz.

1. Actually,

only Spinosaurus

is a dinosaur among those alternatives. Mosasaurus

is a mosasaur, a marine reptile descended from a separate lineage of lizards;

no dinosaurs lived in the seas. Brontosaurus

is the informal name of Apatosaurus

(since it is informal, it should actually be written “Brontosaurus”, as is the

formal custom, but I chose not to here, because it would look odd/suspicious),

which indeed is a dinosaur (a sauropod); “Brontosaurus”, however, is not.

2. This question

was not intended to be ambiguous, but a friend pointed it out: remains of a

dinosaur that resembles Tyrannosaurus rex

very closely has been found in Asia, but there is disagreement about whether it

belongs to the same species, or is a different species of the same genus (Tyrannosaurus bataar), or is a different

species of a different genus (Tarbosaurus

bataar). Depending on how you classify it, the answer includes Asia or not.

What is undisputed is that Tyrannosaurus

rex has been found in North America

and not in South America or Asia (yet!).

3. The picture

shows the teeth of a conodont, an

enigmatic group of invertebrates mostly known only from their fossil teeth!

4. Another trick

question! The typical textbook answer is five

mass extinction events, but there is disagreement among experts about two of

these (the Late Devonian and end-Triassic mass extinction events). They were

not quite as massive as the others (less destruction over longer time), and

therefore do not qualify to stand among the other three. Thus, depending on

your view, the answer can be either five, four

or three.

5. This is the

last trick question, I swear! (I just can’t help it sometimes… haha!) Dinosaurs are not birds! Birds may be dinosaurs, so some dinosaurs were

birds, but all dinosaurs were not birds. Also, as my friend pointed out to me,

penguins, which are dinosaurs, are semi-aquatic, and thus not “strictly”

land-living. There is also an extinct bird group called Hesperornithes, which

is thought to have been at least semi-aquatic as well.

To make this

even more buggy, since B and C are false, so is D, by

definition!

Now to the

second quiz! I promise, these questions will be (a little bit) cleaner… Only

one option is correct in these five. (Or, such is my intention.)

1. Gallimimus is a(n)…

A. Theropod

dinosaur

B. Ornithopod

dinosaur

C. Neornithine

bird

D. Informal name

for Gallicusaurus

2. The

‘mammal-like reptiles’ are formally known as

A. Cynodonts

B. Diapsids

C.

Mammoreptilians

D. Synapsids

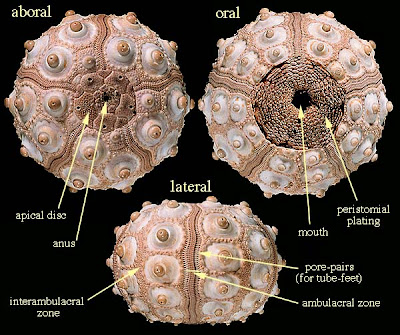

3. What type of

fossil is this?

A. Tabulate

coral

B. Bryozoan

C. Regular

echinoid

D. Irregular sea

urchin

4. When did the

first land plants appear?

A. Devonian

B. Ordovician

C. Carboniferous

D. Silurian

5. What is

another word for the shell of an invertebrate?

A. Tectum

B. Test

C. Urca

D. Carapace

Tuesday, 15 January 2013

PalQuiz 1

Why have I never

thought of this before?

Multiple choice

quiz with four options, in honour of the IB Science Paper 1s (the one exam type

I genuinely enjoyed)!

Hopefully, I

will manage to give at least five to ten new questions every or every second

week.

Of course, many

of these will be for beginners, others for those who are more well-read on

paleontological topics. Maybe, a lot of these names will be completely

unfamiliar to you, but you can usually work something out by just thinking of

what they might mean! Most scientific terms are made to give an idea of what it

means just by the word; a minority, however, seem to be made to do the exact

opposite (‘solid solution’ in geology comes readily to mind…).

Just remember

that this is all for fun, and what you did not know already, you will learn!

Answers will be

published together with the next quiz…

So… test

yourself, and enjoy!

1. Which is the

most awesome dinosaur ever?

A. Spinosaurus

B. Mosasaurus

C. Brontosaurus

D. All of the

above

2. Where did Tyrannosaurus rex live?

A. South America

B. North America

C. Asia

D. Antarctica

3. To which type

of animal do these teeth belong?

-->

(I will give the picture credit with the answers next time!)

A. Theropods

B. Sharks

C. Conodonts

D. Placoderms

4. How many

major mass extinction events have there been in the last 500 million years?

A. 2

B. 3

C. 4

D. 5

5. Which of the

following statements is false?

A. Dinosaurs

replaced their teeth continuously throughout their entire lives

B. Dinosaurs were

strictly land-living

C. Dinosaurs are

birds

D. None of the

above

Science

“All

generalisations are false, including this one.”

–

Mark Twain

I really felt

like writing something new for this blog today, and I also have been feeling

philosophical of late. I particularly enjoy harassing science with critical

philosophy. So, this post will be about some of the general shortcomings of the scientific method.

Correction, it

will only be about one: everything in

science is fundamentally based on generalisation.

There you go!

(That sounds a bit harsh and radical, don’t you think?

Agreed! Science is indeed fundamentally not-true, but that is only because

science is only concerned with things that cannot be proven beyond questioning.

This is because the only things we can know are absolutely true are things that

are true per se (in themselves), e.g.

things that are true by definition – a classical example being that ‘all

bachelors are unmarried men’: this is always true because if it is not a man

and not unmarried, then it is not a bachelor – and such truths, albeit true,

are not particularly useful to us! So, science takes on the tough job of approaching the truths we never can be

100 % sure of – not until we have screened the entire universe for every single

example of the thing we are examining, and that is just not feasible.

In time, hopefully within a week or so, I hope to have

time to prepare a proper account for the scientific method and its

philosophical value. What I wrote here was mostly just to introduce the topic,

and hopefully stir your minds a bit. The purpose of sharing these thoughts is:

first, because I resent how so many blindly accept scientific ‘facts’ as fully true,

when they, at best, may be true in most cases, or true beyond reasonable doubt,

such as the theory of evolution by natural selection; second, because I keep

being told about the scientific method in university lectures, but no one has

really approached the subject of what it really means – what are they really doing? what is good about it? what is

lacking? – all we have been given are descriptions, no critical thinking, so I

wish to illustrate some of the philosophical pits of science.)

Ps. I angled this post to one point of view only: the one emphasising science's weaknesses. I did this maninly to provoke any kind of response, and indeed, it sparked a long debate on FaceBook, so now I am satisfied! The rest of you, rest assured, that I will present the strengths of science as well in the follow-up post! Because, regardless of the undeniable (when you understand them) problems with the scientific method, it is not all that off after all, and it is the best we've got! (so far...)

Ps. I angled this post to one point of view only: the one emphasising science's weaknesses. I did this maninly to provoke any kind of response, and indeed, it sparked a long debate on FaceBook, so now I am satisfied! The rest of you, rest assured, that I will present the strengths of science as well in the follow-up post! Because, regardless of the undeniable (when you understand them) problems with the scientific method, it is not all that off after all, and it is the best we've got! (so far...)

Wednesday, 9 January 2013

You know you were meant to be a paleontologist when...

... you find 11 fish vertebrae in your canned salmon and get excited about it!

Any sane person would take them out, although they were so soft you could turn them to dust by sneezing...

... but only a lunatic would clean them and keep them in a jam jar!

Yep... that's me: nerdy to the bones! The frail arches (the thingies sticking out at the top and bottom) were all broken except for two when I cleaned away the flesh. What keeps stunning me is how uncomplicated the fish vertebrae are – just like a round tree stub with concave faces without any odd protuberances or projections sticking out here and there as in advanced land animals.

I will sadly not make an elaborate post out of this odd event – I have a geology exam to prepare for – but I might just pick them out any day soon and have a little fun... hehehe...

Any sane person would take them out, although they were so soft you could turn them to dust by sneezing...

... but only a lunatic would clean them and keep them in a jam jar!

Yep... that's me: nerdy to the bones! The frail arches (the thingies sticking out at the top and bottom) were all broken except for two when I cleaned away the flesh. What keeps stunning me is how uncomplicated the fish vertebrae are – just like a round tree stub with concave faces without any odd protuberances or projections sticking out here and there as in advanced land animals.

I will sadly not make an elaborate post out of this odd event – I have a geology exam to prepare for – but I might just pick them out any day soon and have a little fun... hehehe...

Wednesday, 2 January 2013

Looking back – a short evaluation of 2012

This blog has

been for nearly a year (the first posts were published the 18th of

April 2012), but since it is a new calendar year now, and I have had a taste of

a little bit of most things that I think await in the near future, I might as

well do some reflection over this blog so far. This will only be a quick,

superficial review, since many of the texts have been quite sporadic and

spontaneous (not to say arbitrary) in nature, so there is little sense in doing

some sort of in-depth scrutiny of values and limitations (and, frankly, because

that seems pretty dull to do on a blog…).

The fieldtrips

dominated the early months, and they were great fun and useful to write about. There

will be a few more fieldtrips in the future, including one in late March to

early April, so if you enjoyed these posts, more are to come, rest assured.

Next came more of a mix between random factual texts, stories from my voluntary

work as the museum and picture galleries from my forest ‘self-trips’. The

sporadic factual texts were partly to fill some spaces, and also to allow me to

write on whims and urges, so I will definitely keep those up. I do not work a

the museum any longer, but I am intending to search for some part-time work the

next term, and hope to have some interesting insights to bring from there too!

Then there was

the fell hiking trip. Epic. I truly hope there will be another this

summer. Finally, was the time when I

moved to Bristol, and there was a lot of things going on, not all related to

paleontology and/or worth writing about, so I had to fill the vacuum with some

old texts and stuff… I hope that has not been disturbing or devaluating – I

just wanted to keep you entertained while I could not produce new, fresh

material. Although, one unusual discussion did come up: the one about the dragonsand hippogriffs! I am sure more of those odd, on-the-verge-of-silly things

will come in the future.

The January

exams are only multiple choice, as I explained in an earlier post, so

there has not been any ‘point’ in thinking outside and about the box; this is

what I need to do for the end-of-year exams, though, and I find it good

practice to write down your musings in a blog or blog-like fashion, since it

makes you really think about your idea, and to check that you have thought

carefully about it, from as many angles as possible, and, finally taking the

essences out and explaining it to people less familiar with the subject.

Hopefully, you will see some original posts in short. Also, I hope this could

spark some discussions with fantastic ideas from your side!

Overall, it has

been really great to run this blog, which has encouraged me not only to keep

this going, but also to start the new blog The Bluest Ice about global

issues. Something I might add is that I was pleasantly surprised by how

(arbitrarily) well the content managed to relate to the title of the blog!

Thursday, 27 December 2012

Anatomical directions (land vertebrates)

Another of my old articles from my previous website. This one is about the names of the basic anatomical directions. Albeit confusing at first, this jargon is actually pretty useful once you get the hang of it!

(I introduced the topic with a silly short poem...)

Right is wrong.

It should be left.

Left right there.

Hehe, no, seriously...

There are four main contrasting pairs of

terms of directions in anatomy. Note that these apply mainly to tetrapods, or

four-limbed vertebrates, to which dinosaurs do belong, but many animals such as

molluscs, insects and spiders do not. However, since this site is about dinosaurs,

these are the most relevant ones.

These terms rely on the fact that tetrapods

have a distinct head, trunk and tail, four limbs, and clear up and down sides.

Dorsal

means toward and beyond the animal’s back, and ventral means toward and beyond the animal’s belly. Note, however,

that most tetrapods have their trunk lying horizontally, unlike in humans (and

kangaroos!), meaning that their back faces upward, and their belly downward.

Therefore, dorsal and ventral may loosely refer to up and down.

So, the

ribs would be located ventrally to the spinal column. We could apply

this to

the skull too, for example by saying that the upper jaw is dorsal to the

lower

jaw, or that the tooth sockets lie ventrally to the eye sockets.

Moreover, stegosaurs

are characterised by large plates on their backs, which we could call

dorsal

plates (in this case, maybe the word dorsal refers more to the fact that

the plates sit on the actual back of the animal, but they are

nevertheless the most dorsal part of the stegosaur).

Anterior refers to structures toward

the tip of the snout, while posterior

is used for things toward the tip of the tail. In simple terms, this means forward and backward, since most tetrapods have their snout facing forward, and

so on. Thus, the forelimbs are located anteriorly to the hindlimbs, and the hip

region lies posteriorly to the rib cage. Ceratopsians, including Triceratops, have a special beak-like

bone (called the rostral bone) attached anteriorly to their upper jaw. Stegosaurs

had formidable spikes on the posterior end of their tails.

Proximal

and distal apply chiefly to the

limbs (and sometimes to the tail). Proximal means closer to the trunk, while

distal means further away from the trunk. Thus, the fingertips are the distal

ends of the forelimb, and the femur (thigh bone) is proximal to the knee cap. Many

theropods had the distal end of their pubis (a bone in the hip region facing

ventrally, or downward) formed like a boot.

Tetrapods, like many other animals, have a

clear midline that separates the body

from top to bottom into two identical but mirror-imaged halves (the line of symmetry). Referring to this

so-called sagittal plane, we use

the terms lateral, meaning away from

the midline, and medial, meaning

toward the middle. The shoulders are generally lateral to the skull, while the

tail would be medial to the shoulders. Some nodosaurs (a type of ankylosaur), eg. Edmontonia, had enormous spikes extending forward and laterally from their shoulders.

These terms can of course be combined. The two subgroups within

Dinosauria, Saurischia and Ornithischia, are usually distinguished by the

former having the pubis facing anterioventrally (i.e. forward and downward) and

the latter having it oriented posterioventrally (i.e. backward and downward).

The characteristic neck frill of the ceratopsians can be said to be facing

posteriodorsally (backward and upward), while it is also expanded laterally

(broadened). In addition, one can refer to structures running along

a bone or an axis: theropod teeth had serrations running

proximodistally along the edge – that is, they extend from the proximal

to the distal part of the tooth.

How would you describe the direction of Edmontonia's shoulder spikes, using the combined formal terms?

This system is rather useful, being

fundamentally simple (although the words may be confusing if you are not used

to them) and concise, and understanding these will surely help you understand

more formal texts, especially descriptions. Trust me: once you get the hang of

it, you will find it very convenient!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)